On MaSuRCA Paper and Algorithm

We wrote about MaSuRCA genome assembler from a University of Maryland group in two earlier commentaries.

How about a Chaotic Genome Assembler?

SPAdes and MaSuRCA Assemblers Performed Best in GAGE-B Evaluation

Yesterday, we noticed some activity on their website and a note about their about- to-be-published paper. So, we contacted professor James Yorke, the corresponding author, and he was kind enough to send us a preprint. Based on email correspondences, Dr. Yorke’s group designed the algorithm for very large genomes, such as the 22Gb conifer genome. So, they were pleasantly surprised, when the program performed well in the GAGE competition for tiny bacterial genomes.

After going through the paper, we find similarities with the Ray assembler, and that is likely why both of them manage to get longer scaffolds. MaSurCA claims to use neither de Bruijn graph nor OLC approach, but a third approach.

**Super-reads, a new alternative. **

In this paper, we propose a third paradigm for assembly of short read data, based on the creation of what we call super-reads. The aim is to create a set of super-reads which contains all of the sequence information present in the original reads despite the fact that there are far fewer super-reads than original reads. For the ideal error-free case, see the Theorem below.

The basic concept of super-reads is to extend each original read forwards and backwards, base by base, as long as it can be done so uniquely. The concept can be explained as follows. We create a k-mer count look-up table (using an efficient hash table) to determine quickly how many times each k-mer occurs in our reads. Given a k-mer found at the end of a read, there are four possible k-mers that could be the next k-mer in a genomes sequence: these are the strings formed by appending A, C, G, or T to the last k-1 bases in the read. Our algorithm looks up which of these k-mers occurs in the table. If only one of the four possible k-mers occurs, we say the read has a unique following k-mer and we append that base to the read. We continue until the read can no longer be extended uniquely; i.e., there is more than one possible continuing base or we have reached a dead end and no base is ermissible. We perform this extension on both the 3 and 5 ends of the read. The new, longer string is called a super-read. Notice that if two reads have an interior difference by even one base – as, for example, would occur if they derived from two non-identical repeats or from two divergent haplotypes – then they will generate distinct super-reads. Of course super-reads can easily be computed using a de Bruijn graph. The point is that once the super-reads are created, they together with mate pairs that connect super-reads – collectively replace the de Bruijn graph. Incorporation of mate-pair information is carried out using the OLC assembler. The two most important properties of the super-reads are:

each of the original reads is contained in a super-read (so no information has been lost); and

many of the original reads yield the same super-read, so using super-reads leads to vastly reduced data set.

Jim will be happy, if you use the program. He will be even happier, if you pronounce MaSuRCA as mazurka as in this polish dance, or in Chopin’s Mazurkas -

-————————————

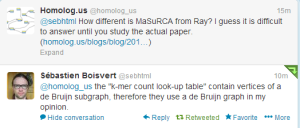

We asked opinions from both @sebhtml (the author of Ray) and James Yorke about the similarities and differences between two algorithms. Sbastien commented -

We will add the response from Jim below, when we hear back from him.